Having arrived in Nepal, having found a dwelling, having taken refuge in the three jewels, the wandering yoginī set out to receive teachings of the precious sublime dharma. Luckily for her, the karmic seeds one holds in the field of dharma practice are easily sprouted in the conditions of this land of the dakinis, and in a few short weeks the opportunity presented itself to join some very special teachings by a Bhutanese teacher called Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. Don’t worry if these names feel foreign and long, they do for her too, and it is simply another reminder of the fact of habituation. When the yoginī of this story introduces herself by her own name, Tamara Dawn, the people of Nepal have to stop and second guess as well. Everything in the relative world of cause and conditions is the playing out of our habituations. The more one cycles around in the field of dharma talks, the more names like Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche roll off the tongue like butterscotch. Until then, we might abbreviate to DKR.

This introduction may seem like a tangent, and you may be wondering what the subject of our reflection will be. Convention might have it that a clear topic ought to be determined within the first paragraph of any readable text, and we might be off to an irregular start already. But actually we have already begun to establish our focus. Our topic is peeking out through these words and winking, like a gopi enchanting Kṛṣṇa who reciprocally, and in perfect synchrony returns the blessing. We can recollect the teaching that when we come to true appreciation of the intricacy by which our conditioned habituation lends our perception, everything tends to become quite humorous. The idea of names even, of calling one thing Tamara Dawn and one thing Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, can bring a slight smirk. When we realize the complete miraculous void of inherent meaning in any subject or object, and the intricate dependent nature of all arising phenomena, we can’t help but smile, laugh even. It has been said that when the Buddha saw the suffering of all beings, and its end, he smiled. Who said the buddha said that, I cannot confirm, but alas, perhaps he did.

Our wandering yoginī was smiling as she sat in the linen covered chairs at the Kathmandu Hyatt amid a blended crowd of Nepali people and foreign tourists in a ratio of coffee with a little side of cream. Her long neck peeking her head slightly above her fellow seekers of ultimate liberation, patiently awaiting to receive the instructions for the way out of saṃsāra. Some Tibetan grandmas were enthusiastically taking videos of the back of people’s heads and then rewatching them over and over, perhaps wishing for the enlightenment of each of the subjects, or perhaps just dealing with an undiagnosed case of social media induced adhd. Perhaps not even Tibetan grammas are immune to the densities of the legendary Kalī Yuga. The Iron Age induced air conditioned opulence was a refreshing contrast to the humidity of her regular student life surroundings, and she contemplated the drizzle of residual judgment from her own conditioned mind, that condemned riches, softly dissolving into emptiness as she remembered to at least try to fathom the infinite.

Suddenly the crowd shuffled and all the bodies began to rise as if all were fingers attached to one common hand ready to reach for one of the door knobs to liberation. It is tradition to stand when a Rinpoche, or any esteemed teacher really, enters the room to begin to teach the sublime dharma. It might seem on the surface as though it is to benefit and respect the teacher, but the yoginī wondered if it likely was more for the benefit of the people rising. A brief moment to humble oneself and put another first. This opportunity to practice one of the basic teachings of putting others before oneself, of valuing others more than oneself, is such a difficult thing to catch for most common people. Perhaps the chance to generate at least a little merit by such traditions was part of the cause for their development. So many mind tricks in the buddhist methods. A dose and prescription for every kind of the 84,000 defilements.

The Rinpoche of this weekend seminar that is the subject of our reflection, titled “Nepal and Buddha Dharma”, founded an organization by the title of 84,000, an initiative to translate the actual doctrines of the buddha, the 84,000 prescriptions so-to-speak from Tibetan and Sanskrit into English and other languages. The yoginī was excited to learn from somebody who shared her appreciation of preserving the scriptures. On top of this, the quite famous DKR is known not just as a prominent buddhist lama, but also as a highly acclaimed film director and producer. An eccentric type of Rinpoche that felt more like home to this rooftop dancing, psychedelic munching, sort of aspiring yoginī. Just a week before hearing about his arrival in Nepal and the upcoming teaching seminar, the yoginī had seen one of his films titled ‘Searching for a lady with fangs and a moustache.” The title of the film itself is likely enough to spark your interest if you have any kind of fascination with the occult, and/or karma for the Tantrik teachings. For the yoginī the viewing of this film followed by the learning of the upcoming teachings felt like a wink from the dakinis, and she simply had to follow the vibe.

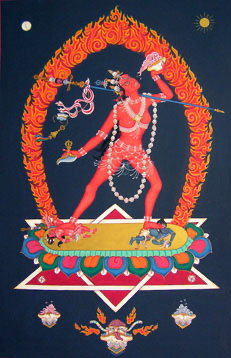

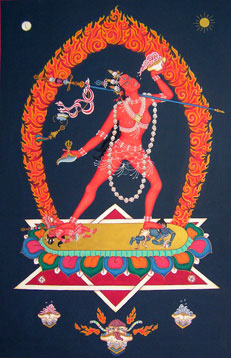

Now, dakinis get all kinds of hype nowadays as the world gets increasingly interested, based on our cultural sex obsession really, in the general iconography and aesthetic of the Vajrāyana teachings of buddhism, the Tantra teachings. Our yoginī is far from immune from such conditions, and the thought of flying sex goddesses skilled in the 64 arts of love who drink blood and dance across the sky helping all mind possessing beings to recognize the essential nature of what they possess was of incredible interest to her wandering heart. DKR reminds us not to be deceived by our conditionings’ desires for the Dakini to be a kind of spiritual rock star bad ass babe, and to remember that really they are bitches. But perhaps that too is enticing to the feminist revolution where we are not only reclaiming words like Bitch, we are rising up to the Pussy revolution. The mystique of an ancient deity-buddha-goddess archetype may very well be just the bridge we need in this modern confusion to trace our way home to recognition. Perhaps the queen of the dakinis can serve as a kind of Beyoncé idol to at least begin to steer our minds towards the illumination of all the qualities of the awakened ones, which is what the dakinis are said to do. I sound like a skeptic, saying things like “are said to do”, but that’s just a pretend attempt at scholastic impartiality.

Though Rinpoche didn’t speak too directly about the dakinis, he did speak to the content that their emanation bodies symbolize. Which could perhaps be considered the more important, albeit less sext, aspect of the mind training we engage in when practicing the sublime dharma. Vajrayoginī, for example, the queen of the dakinis, is not to be thought of simply as her emanation body, the body we see in images, or if we’re lucky and ripe, flying up to our balcony and leading us to her pure land. This materially organized body is meant as a symbolic illumination of a principle, and this principle is the complete awakening to the three doors to liberation. Even her maṇḍala, the duo-tetrahedron, is a representation of these three doors. Two triangles, in mirror image, as if to say, everything, and nothing.

So what are these three doors? Our yoginī was also wondering. But in the natural way of any skilled, and realized teacher, the point becomes a wave and remains a point for the duration of its infinite transformation, and things arrive in a step by step way that doesn’t always appear linear, let alone timely. I mean, when we start talking about Buddhism, we usually are at least peripherally aware of the relativity of time, and in such a way the very notion of urgency and rush again can lead to at least a toothless smile. It took most of the weekend to circumambulate the three doors of liberation, and somehow we lingered extensively in the first doorway, which seems fitting, this first doorway being the recognition of emptiness. The emptiness of the self, or no-self. The dissolution of the fiction that anything has a fixed and determined identity, and the evolution of the wisdom that everything we can perceive, including our perception itself, is a relational field of dependent origination.

This is the essential door. The only door you’d need, if you figured out how to actually get your head through it. Or let the door frame chop your head off clean enough as you enter that it actually falls off and you drop into the next door of signlessness. Or, as DKR said in his signature whispy accent “Characteristiclessness….” The sound of his voice hissing this non-existent word felt like a naga, a snake spirit, performing an incantation into the winds of the yoginī and she sensed a kind of smile in her spine. Characteristiclessness. An unimaginable phenomena. Which is the point of course. Well, that wavy wavy, spiralling, invisible, signless, and scentless, point of course.

Who would you be without any characteristics? What would it be like to perceive the world of rising and falling phenomena, all impermanent appearances as though they were void of characteristics? It almost feels like these two doors are kind of revolving doors, like they’re actually the same door, just from a different angle. And we’re like some kind of silent movie actors having been slipped a few tabs of acid and stuck in a revolving door between the worlds of emptiness and characteristiclessness. Perhaps the hardcore buddhist doctrines would cringe at such a metaphor, but what to do? Buddhism is far from a culturally contained existent anymore, and really, even its founder, the kśatriya rebel of Brahmanic convention, was an elaboration within the impermanent metamorphosis of consciousness shape shifting through timeless spaceless infinity. This is a perfect Segway into two of the cautions our beloved DKR served out for the eclectic crowd there in the Hyatt ballroom.

There are two extremes which can be fallen into when we begin to contemplate these two first doors. One is called Eternalism, and the other is called Nihilism. The second half of the above paragraph is leaning towards Nihilism. The bleak, vacuum-like meaninglessness of thinking that emptiness means nothing absolutely exists and absolutely nothing exists, and so we would be absolutely insane to give a tiny fuck about anything at all. I mean, the thing we’d be giving a fuck about wouldn’t even exist, right? Essentially, nihilism in regards to the view of emptiness turns the mind into a kind of reverse schizophrenic. Rather than seeing hallucinations and hearing voices, you begin to think that the things you really are seeing are hallucinations, and the people talking to you at your desk job are just voices in your head. Which of course on some level is accurate, but not completely. This is considered an extremist view of the teaching of emptiness, and clearly is not healthy. Likely we’ve seen or heard of something like this, where someone has a spiritual experience and touches their mind to emptiness, but is ill-equipped to hold the complexity of the paradox that is necessary for the correct and paradoxic laden view of emptiness and ends up isolating into a kind of void concept where chain smoking and and munching on chicken curry is seen as equally spiritually advanced as any of the conventionally pious virtuous activities. Dangerous, perhaps.

The great Indian schools of thought were well versed in paradox, and so the cultural context within which these teachings of the sublime dharma arose, the three doors to liberation, provided a kind of hospitable foundation for their exploration. Even then, these cautions to watch out for the extremism of eternalism and nihilism were posited as important. Nowadays, we are perhaps less cultured in the holding of paradox, of two truths that seem to oppose one another, but actually don’t, and in our youthful vigour are susceptible to falling into one of the two extremes. So, best to check for yourself, lest you fall into a kind of spiritual psychosis.

The other extreme of eternalism presents as a person who takes these teachings of Emptiness and Signlessness to mean that everything is of utmost importance. Realizing the intricate connection between all beings, all appearances, all phenomena, though only relatively “real” so-to-speak, the fixation on generating positive conditions in order to experience a kind of relatively “perfect” reality (whatever that means) arises like an addiction or obsession. The game changes from trying to win at saṃsāra (the common autopilot mode of a sleeping, unawakened being) to trying to “hack” saṃsāra as if it is ultimately different than nirvaṇa and the spiritual goal of the buddhist is to frantically or with a kind of neurotic intensity try to stack the cards in favour of favourable conditions. An eternalist becomes a person with a lot of social anxiety, always wanting to do the “correct” thing, to avoid karma, and desperately get out of suffering. They cling to “their view”, develop arrogance in their blindspots, and tend to assert their opinions with a kind of desperate vigour. The lack of an existing self turns into a kind of fixation on an eternal nothingness that seems a lot like something.

I should say now, as your yoginī speaking to you, yes, it was me in the audience, that all this is but my own interpretation of the teachings. One might hope that that is obvious and unnecessary to say, but in sheepish respect of social convention, gasp, I will enunciate that these are but my interpretations of these teachings. May this pause in our exploration serve as yet another example of the teaching of Emptiness. Even the teaching of emptiness, you see, does not actually exist. The teaching of emptiness is something different to you, the reader, or listener, than to me, the writer. The teaching of emptiness is different to DKR as he spoke it out into the ocean of the few hundred mind possessors in the crowd, for whom the teaching of emptiness was, and continues to be, something different for. Point to the centre of the sky my love! I’ll meet you there. We can drink some tea and try to know each other.

Actually, I’m getting quite thirsty. Could you pass me that jar of water? Now, this request will work, probably, because you and I likely have similar enough conditions that we have the capacity to see, taste, touch, smell, hear and cognize a jar of water in a similar enough way that we would agree on it actually being a jar of water. But, if I asked a water buffalo to pass me that jar of water, he certainly wouldn’t be able to. Not just because his hooves can’t grasp the jar of water. His mind simply doesn’t fathom any jar of water. Let alone if I were to ask the billion microbes living within that jar of water, to pass their abode to me, so I could drink them to alleviate my momentary thirst and in so doing generate their suffering. Perhaps you get the picture.

So nothing inherently exists, and yet we are cautioned not to fall to either of the extremes of eternalism or nihilism. How do we manage this? The key is holding the paradox, the both/and wedgie, of seeing both the relative and ultimate nature of phenomena. Ultimately, no phenomena has an inherent, self-arising, self-existing, independent “self” or “nature”. Yet, relatively, we do have a collection of aggregates which appears as a linear progression and conglomerate of meaning. We have a relative “story”, within which we are living among relatively appearing “other stories”, which we would best do to respect. Sometimes this dance of both-and is referred to as riding the razor’s edge. In Buddhism, the term madhyamīka, or the middle path, is elucidated. It is the remedy for falling into either of the extremes, and requires a bit of sharp skill to simultaneously hold both views as we interpret through our perception, our relative existence, and infer through wisdom our ultimate non-existence. If we can walk through this door of the correct view of Emptiness, we attain Liberation.

Let’s look a little more at that second door, that hissing characteristiclessness that is the kind of flip-side or Siamese twin to Emptiness. Signless. Without sign, or symbol. Without characteristics, free of the confines of description and elaborations. Sometimes it is described as ‘the sphere of freedom from elaboration’, which of course is but another finger pointing as a quality-free moon. All these signs, being registered by the minds which have the appropriate causes and conditions to serve as cognitive receptacles for the fragment of data that forms the collection which is perceived as any ordinary object. A book. A soft blue cat. That fragrant vine of jasmine. All these signs and symbols which organize the mind to formulate a division between that which is observing, or reading “the book”, and that which is the book itself. This vast complexity of rising phenomena that are the conditions to allow the skin to pet the fur of a blue being who might never refer to himself as a cat, and certainly doesn’t realize he is blue. What would that soft blue cat feel like to the coat of a colourblind porcupine?

It is now known through scientific experiments that what the Buddha taught in regards to this lack of inherent qualities of any existent, is a fact. The microscope worshiping cult of science has uncovered that, for example, the human eye can only register a small segment of the full spectrum of light. Does that mean the other ranges do not exist? Are they not perceived by some other kind of eyes, with different cones and rods, with different computations? No, it means that all of the characteristics we perceive through our senses are but relative realities, and there is nothing ultimate whatsoever about them. This is a door to liberation! Walk through it my love and meet me where we can’t taste the rainbow, but can happily enjoy our tongues according to our current and fleetingly impermanent conditions. We can both see the rainbow, and know we will never touch it.

This points to one of the main insights of the Buddha, the awakened one, here emanating as our beloved DKR casually delivering the keys to the doors to liberation just in time for the tea and biscuit break. The importance of relying on knowledge gained through inference, and not solely relying on knowledge gained by direct perception of the senses. If we remain stuck in the limited scope of our material sense perceptions, that which we can see with our eyes, taste with our tongues, feel with our bodies, hear with our ears, smell with our brains, or think with our minds, we limit our knowledge to this very small segment of the infinite that we are causally adapted to. To a Buddhist, this could be thought of as limiting our knowledge to a very basic, or gross, level when we might gain through inference a much wider scope of knowledge.

The Buddhist teaching that mind is the cause of mind, that matter is not the cause of mind, and that thus mind continues from one form to another, and is not dependent on any momentary form for its existence, is arrived at through this kind of knowledge gained through inference. If we were to rely solely on our sense-faculties for knowledge of the nature of existence, we would certainly fall to materialism, and consider our lifetime as a singular and relatively meaningless occurrence. “Truth goes beyond all reference”, DKR said, reminding us that our continual grasping at reference is actually the source of our suffering. Without references, we become signless, symbol-less, and characteristic-less free beings, unbound by the illusory definition of name and form. This kind of knowledge cannot be arrived at by referencing, through direct perception of the senses, and so those whose propensities lie in sense-perception may have a difficult time chewing without teeth the meat of this teaching.

Perhaps taking a moment to describe the benefits of the prescription of recognizing that all phenomena are beyond sign, symbol and characteristics. Much like the opposite of listing the potentially harmful side-effects of a particular pharmaceutical, let us take a moment to consider the mind-freeing effects of realizing this second door to liberation, and actually walking through it. So much of our suffering, one might go so far as to say all of our suffering, is caused by this constant and uninterrupted stream of referencing. Self-referencing, referencing to others, to time, to space, to culture, to convention, to construct and conditioning. All these data points floating around in our meaning-making mind evaluating and judging the value of our experience. All these references, which exist only in relation to each other in a kind of eternal hand-me-down of incestual intellectual projection that we culturally and collectively determine as the way things are. An intricate trap, where we ourselves swallow the key and spend our precious human lives banging our heads against the door we’ve locked ourselves out of.

Take depression for example, we become afraid of something really terrible happening and fall into a depression worrying about either this something coming into being, or perhaps worrying something we want to arise, won’t. Where do these fears and hopes come from? They come from referencing. The only way, say for example, a sociopathic corporate boss of yours loading you with extra work becomes a cause for depression is when it links into the web of references established in your mind. It bumps up into the neural network of your references which tell you that you don’t like extra work, that this man is evil, that you never get a proper weekend off, that your father was always pressuring you a kid, that you never caught up in school, that you’re worthless, that someone else you know doesn’t have such a bad job, that if you only applies yourself you’d be the boss. All these stories. Narratives woven into narratives into a big matted ball of indistinguishable thought-constructs that have you decide that this ultimately non-existent phenomena is absolutely real, and you are the receiver of its negative essence.

DKR explained his thoughts on this rising dissatisfaction as an effect of modernity. He spoke about how as we establish a kind of social equality paradigm, where anyone can be anyone, the capitalist American dream basically, that we simultaneously establish a fertile ground for dissatisfaction. No longer is it okay to simply be a farmer. Even in Nepal, for example, the youth of the villages flee their farmer heritage in search of wealth, fame, name, and gain in the urban jungle of Kathmandu, because, the future is in technology, and happiness is thought to come from changing one’s circumstances. Changing the reference points. The Buddhist teachings offer the notion that this is far from an actual solution. That trying to change the reference points, to manipulate the contents of the mind, is but a swirling drowning mess. Rather, we are guided to change the mind itself, the processor of the contents, the meaning-maker, story-writer, the producer of our living dream.

Our beloved teacher, nonchalantly waving his arms in a signature twist of the wrists gave us the example of Alexander the great’s attendant. “Do you think the attendant of Alexander the Great was thinking how bad it was to be attending to him, thinking something if only he could be great himself? No, this is a modern problem. He was probably quite happy bringing him the grapes!” This is a worthy contemplation, it seems to this yoginī waxing poetic with you about the nature of emptiness. If one of the sources of our suffering is the addictive fantasizing quality of the modern mind to perpetually live in the future possibility, in the trap of comparison, perhaps the remedy is quite simply to embrace this door to liberation, and drop the signs, the symbols, the characteristics and just observe the particular spectrum of sound-light-sensations we are privy too in each moment.

He gave the example of observing one’s hand. Not in an ordinary one, as in looking at the unit of the hand, with the conception intact, but as in observing it in all its details without making a narrative about it as a whole organization of elements. He said that this is a practice sometimes given to monks, to just observe, for weeks. He said that eventually, after sometime of practicing the concept of the hand begins to let go, and the observer can start to see the different aspects of the hand, and that without the whole construction of the concept of the hand, the whole notion becomes quite humorous. Funny. Then the thought of people going around getting manicures becomes deeply humorous. Not evil, bad, or contrite, no-no, just funny. The whole thing of so-called reality becomes funny, when we realize the emptiness of the self. The thing is, we have lifetimes of habitual patterns of conception to deal with. Layer upon layer of habitual ways of perceiving and conceiving of reality, and collectively as well, culturally, so the process of dissolving the stronghold these conceptions have on the limitless of awareness requires training the mind.

It’s also quite a paradox to think about this second door to liberation in the context of Tibetan buddhism. For anyone who has any knowledge of the facets of practice and ritual within the Mahāyana and Vajrayāna teachings to be without sign of symbol seems quite absurd. These turnings of the wheel of dharma are completely laden in symbols, detailed and intricate visualizations, and steeped until soaking in mantras. This is where again the finest of paradoxes is required. Like fire, we need to stoke the fire with wood, but the wood burns away within the fire. In this way, we feed the awakening of liberation with signs and symbols, training and orienting the mind, we kind of use these deity imageries and fantastical ornate emanations as bombs for cultural hang ups and conditionings, remaining unattached to the wood as it burns away in the fire. Yet, we continue to stoke the fire with more and more wood. We continuously map our minds with symbols, while retaining the recognition that the symbol is not the actual nature. The dakini is the wisdom of all the buddhas, of all the awakened minds. And even these words retaining the meaning can with practice burn in the fire of awakening. Even the manner of engaging in philosophy is yogic mind training in the diamond cutter wisdom path of the Buddha. Our minds must be limber to hold these paradoxes without crushing them, yet firm enough to crush our cultural hang ups and conceptions.

Which I suppose in some roundabout way brings us to the third door. Maybe this door is there for those who didn’t make it through the first two, or perhaps for those who are spending countless eons flying between the doors and trying to scoop up as many living beings in their 100,000 arms as possible to bring the minds of all the mind possessors through to liberation. The third door is called “the fruit is beyond aspiration.” Fruit here referring to the result, the result of both the aspirants practice of the dharma, and of all the cosmos of beginingless mind. There is no goal to aspire to, there is nothing to reach for, for it is already present. I know I know, perhaps your mind is tired of this paradox treadmill. If that’s the case, it’s quite fine. According to this view, you need not force the revelation. Go, have a nap, drink a cappuccino, or climb Mount Everest. The nature of mind will enjoy these activities with you, or, more accurately perhaps, will remain unaffected and charactersticlessnessly chill.

For those who like these mental exercises, we can continue to look into this next paradoxical doorway. “The fruit is beyond aspiration” is saying that ultimately we cannot actually unveil the Truth by asserting effort, for the nature of the Truth is effortless, spacious, beginningless awareness. And so spiritual weight-lifting so-to-speak will not actually flick the switch. But, we can observe the law of cause and effect, that every rising phenomena has a cause, and aspire to generate the cause for the effect of our awakening. This is where the buddhist tradition is so versed in the myriad of ways to practice what we call “generating, collecting, or accumulating, merit.” Merit refers to the virtuous quality, or impression, on the mind that comes from virtuous actions carried out with the mind in meditative concentration on the teachings of the buddhadharma. This means, actions such as making offerings like butter lamps, flowers and incense while holding the view of emptiness. It can mean chanting a particular mantra while visualizing oneself merging one’s mind with the mind of the buddha. It can mean elaborately visualizing a mandala containing every precious object and quality one can imagine, and offering it to the buddha. Not because the buddhas want, need, or particularly fancy your offerings, but because by you engaging your mind in the concentration upon such a subject, you shape your mind into the shape of generosity, or one of the other virtues, and thus begin to shape the subtle body-mind into the pattern of awakening. Shape, of course, being a metaphorical term here. For there is no form in this mind map. The aspiration is to turn one’s mind into the mind of the buddha, where ultimately all aspiration, again, is kind of humorous. We can imagine, what it would feel like if we were an omniscient buddha, the most attained and perfected being we can fathom, who has everything one can ever wish for, and thus wants for nothing, and a being quite contracted in their personified singularity, came and offered us a flower. Surely, we might smile. The fruit is beyond aspiration, reminds us that upon seeing the fruit, aspiration will dissolute. Yet as practitioners, we hold our aspiration bodhicitta, our desire to benefit and serve the enlightenment of all, kind of like children picking dandelions for their mothers. Beautiful in its humility.

Perhaps we can wrap these doors to liberation up in a nice analogy, like a door hanging to calm and centre the mind. Rinpoche shared this analogy on the third day of the teachings, and it seemed like perhaps a kind of parting gift in case we hadn’t quite distilled what he’d been sharing on the nature of emptiness and dependent origination. Which we can with reasonable certainty presume we hadn’t. Imagine you are having a terrible horrifying nightmare. You really aspire to get out of that situation. You are actually sleeping in a very nice, soft bed. Totally safe in that bed, but your mind is in the nightmare, being chased by giant spiders, or fleets of writhing serpents. Whether you aspire to get out of the nightmare, or not, you are already fine, sleeping in the soft cozy bed. Finally, someone notices you there, and wakens you. Maybe by pinching you, or pouring a bucket of cold water on your head. You wake up! You realize all along you weren’t really being chased by spiders. You were just there, in that soft bed.

In this metaphor, the nightmare is like saṃsāra, and the bed is like nirvāṇa. You’re already in nirvāṇa, from the vantage point of nirvāṇa. Practicing the dharma is like throwing a bucket of cold water on your panicking head. By thinking that the awakened state is far off in the future, some unattainable, far away, state beyond our scope, we turn the buddha into compacted phenomena. We make the buddha subject to the limitations of time, which by definition, makes what we think we are fathoming as the buddha, not the buddha. Buddhahood, by definition, cannot have an expiry date. This is where we can imagine that perhaps we can let go of our cultural programming that has us thinking “no pain, no gain”, and trade in this heavy, taxing fabrication of the mind for a new slogan. “No pain, all gain.” But hey, what do I know? I’m just a weird little aspiring yoginī drinking coffee and eating biscuits at the Hyatt ballroom in Kathmandu.

I do love your mind! The is dense stuff for my brain, but I really appreciate that you present it in a light, refreshing way that helps me navigate through it. Thank you <3